In

Self-Interviews, James Dickey wrote, “I think a river is the most beautiful thing in nature.

Any river.”

The past week took me to several rivers, streams, and creeks—in the company of new and old friends. It was just what I needed after a couple of whirlwind weekends. The first weekend was spent reading a selection of my poems in Santa Rosa at the Londonberry Salon. What a delight. The next was spent pitching

Junk Sick, the script I co-wrote with my brother, Trent, at an event called PitchFest! down south in Burbank. It was intense. Months before the Londonberry Salon reading and PitchFest!, I signed up for a trout clinic at Ralph and Lisa Cutter’s California School of Flyfishing. The timing couldn’t have been better. I needed some river-time.

A two-day program, mornings were spent studying hydrology and entomology in a classroom setting. Ralph understands rivers like no one I’ve met, including my Fluvial Processes professor back at Arizona State—who was top shelf. Ralph’s knowledge is unique in that it includes countless hours underwater, wearing a mask and snorkel, crawling along riverbeds like an

ephemerella tibialis.

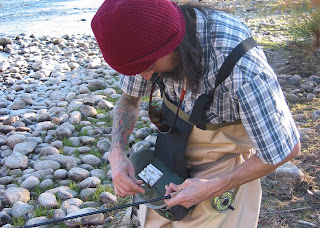

The afternoons were spent on the Truckee River practicing wet- and dry-fly presentations and line-management techniques. The Truckee drains Sierra snowmelt in the Lake Tahoe area and flows north, then east, for 140 miles—into Nevada’s Great Basin. We spent our time downstream from the Town of Truckee in a section of the river that is a designated Wild Trout Stream. Only barbless flies are allowed and catch-and-release is the ethic. Ralph taught us a technique for fishing a streamer that allowed us to swim it both downstream and across the stream. Using a goblin—sans hook for demo purposes—one of the most adept students, Steffan, provoked a wild rainbow. The big fish crushed the streamer and made instant believers of us all. I’m eager to see how a steelhead will respond to this presentation.

Ralph and Lisa have a way of simplifying the complex, and making sure you know what really matters. For example, Ralph explained the role water temperature plays in fish behavior. Understanding why and how trout react to changes in temperature helps the fisher find the best lies on any given day. Ralph suggested we all buy a thermometer before we spend $700 on a fancy new fly rod—as it will do more to help us catch fish. I’ll offer a corollary of my own. Take a class with the Cutters before you buy that rod. Or the thermometer.

Those two days on the Truckee would have been more than enough for me to declare the entire week a success. Fortune, however, continued to smile on me. My buddy David and his wife Carol were in the midst of their annual two-week summer vacation in a rustic cottage near the Sierra Buttes. They invited me to swing by on my way home. If you love rivers, the route from Truckee to Sacramento lies not on the Interstate. Instead, it passes through the alpine meadows around Sierraville, up and over Yuba Pass, and down along the North Yuba River through Sierra City and on to Downieville. David promised to take me to a couple of his favorite, and secret, headwater spring-creeks and introduce me to the redband trout. Part of me thought I should get back home and back to work, follow up on the pitches I’d made just days before in Burbank. But I couldn’t resist David and Carol’s offer. As my wife will attest, I’m not any good at resisting temptation. This was actually a done-deal from the get-go.

The landscape was spectacular, with abundant springs, wildflower meadows, and a golden-colored Black Bear that gave us several angry looks. “Interlopers,” he muttered, before lumbering off into a stand of pines. Like the bear, the rainbows in these remote creeks are wild, native, and used to calling the place their own. And they hit a caddis dry with reckless abandon. I had great success with the downstream-dead-drift technique Lisa Cutter taught me two days earlier—once I remembered to be patient when setting the hook on a downstream take. This adjustment came after jerking the fly away from more than one eager mouth.

The fish we landed ranged from three to ten inches in length. In the first creek we fished the rainbows’ coloration had adapted toward a tint that matched the yellow-ochre of the rocks along the bottom. In contrast, the fish we caught in a creek that meandered through a boggy meadow were tinted a rich red to an almost blood-black. These are the redband trout David told me about. He made sure I saw the distinctive white tips on their anal, dorsal, and pectoral fins. Despite being in the second-worst mosquito swarm of my backcountry life, there was nowhere else I wanted to be. Another nod to the Cutter family—and Deet—is in order.

Four solid days of fishing and friendship revitalized me. The brain cramp I’d developed during twelve pitches to twelve production studio representatives and movie agents, during two two-and-half-hour pitch sessions, was eased as gently as the precious fish David and I released back into those streams and creeks. Back in my truck and following the North Yuba home, fresh ideas for poems, stories, and scripts were rising in my creek-clear mind. When I hit the interstate my cell phone rang for the first time in two days—just as I entered coverage. It was my buddy Adrian, wondering if I could get away the next day to drift the Lower Yuba River with him and Riley. Riley is Adrian and wife Teresa’s amiable Irish Setter. “I know it’s a last minute thing,” Adrian said.

Adrian runs Anchor Point Fly Fishing and guides the Lower Yuba, among other northern California rivers. Any chance I get to spend time on a river in his good company is time well spent. He is also a talented casting instructor and shares his knowledge generously. With his continuing help I’ve become a decent enough two-handed caster to be able to fish effectively for my favorite trout in the rainbow family, the steelhead. Switch casts, spey casts, snake rolls, and circle speys are not just new ways for me to hook myself in the earlobe with a streamer anymore. Adrian’s offer was clearly another I could not refuse. The only problem was I had a meeting the next day at 5:45 p.m. that I did not want to miss. “No problem,” Adrian said, and it was on.

The Lower Yuba differs significantly from the freestone river and spring creeks I’d explored during the previous days. The Lower Yuba is a tailwater fishery, created at the outflow from Englebright Dam. The trout-friendly water temperature is consistently cold year-round because water is released from the lower depths of Englebright Lake. These are optimal conditions for the resident wild rainbows and for the seasonal spawning runs of steelhead and salmon. Adrian and I both like to swing streamers so we scouted for productive runs. I always look forward to casting a new rod from Adrian’s arsenal and found myself adding several of them to my after-we-sell-a-script list.

The surprise of the day was drifting into a run of rising fish at high noon. Drop anchor. Tie on a caddis. The fish were taking but I was missing the hook-set—again. One aggressive rainbow followed the fly I jerked out of its mouth all the way into a magnificent, aerial leap. Adrian and I passed the rod back and forth between us and we finally hooked a silvery-scaled rainbow. The set came just after Adrian ran a perfect dead drift with no takers. He handed me the rod to take my turn with the next cast just as the caddis skated. Fish on. We each claimed half-credit for the fish.

When I arrived at my 5:45 meeting that evening I was still wearing the river and a cologne of sunscreen. Being reasonable persons, my buddy Bill and I chose DeVere’s Irish Pub in downtown Sacramento as the place to meet for our strategy session, and Guinness as our fuel. Bill is another of the wonderfully bright people I’m fortunate enough to know. On the cutting edge of technology, he’s helping me make practical use of new media technologies to bring attention to my writing. At the top of our to-do list was figuring out how to make the most out of my pitches at PitchFest!

Naturally, toward the bottom of our second pint, our conversation started to meander, and we made plans to get out on a river together.

Any river.